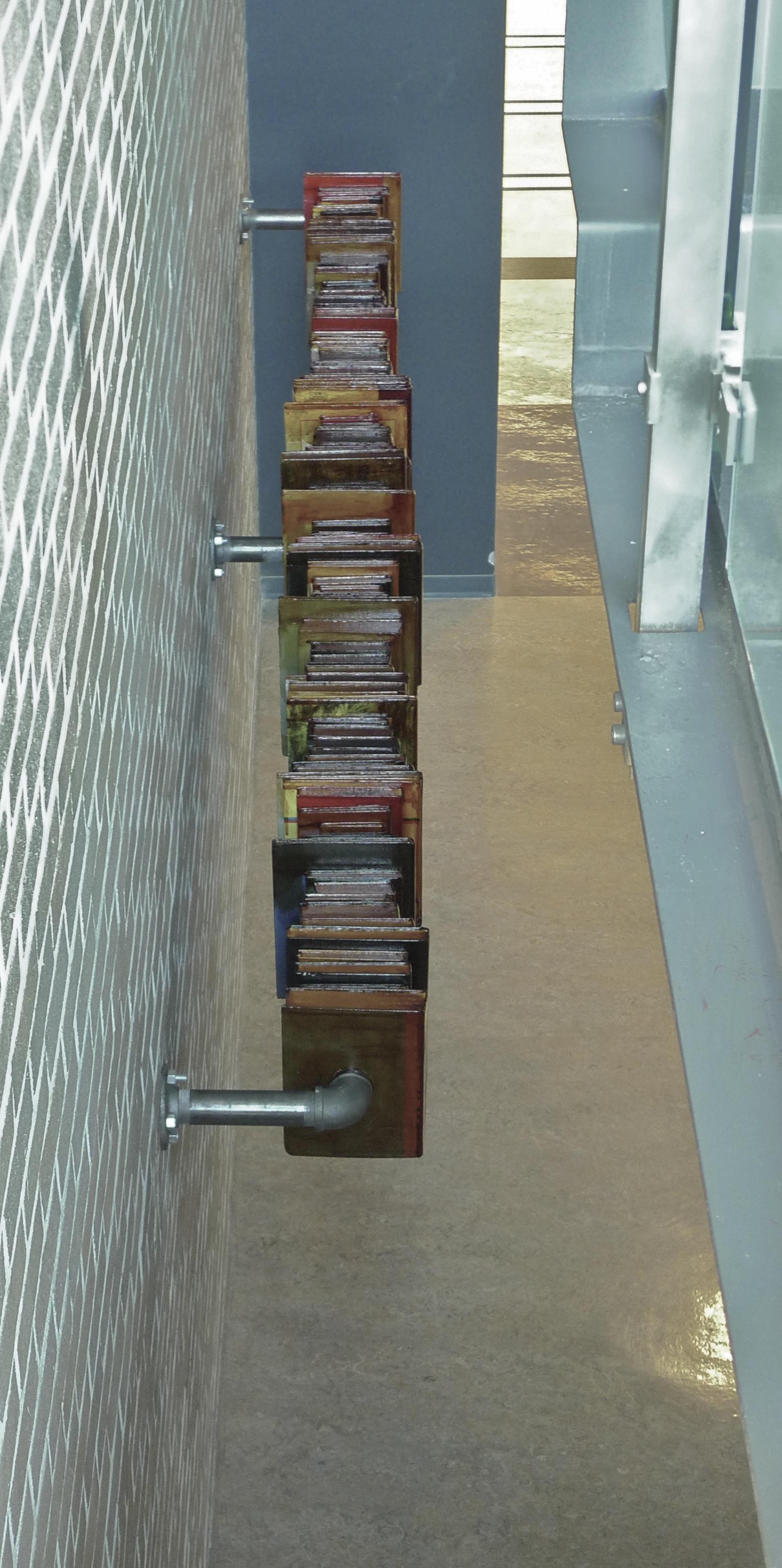

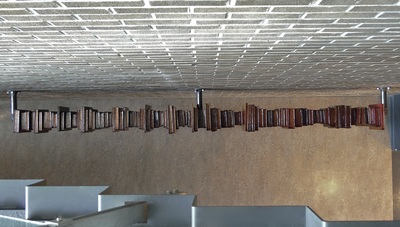

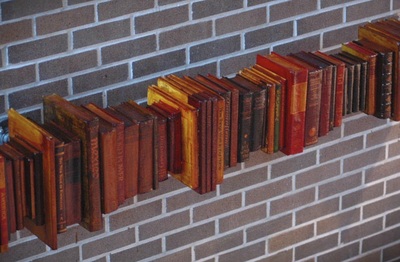

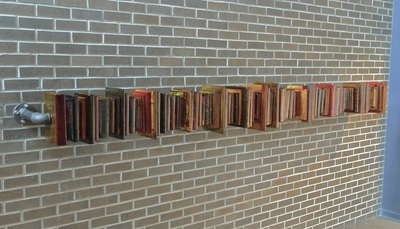

Suspended Sentence

Thomas G. Carpenter Library

University of North Florida, 2013

|

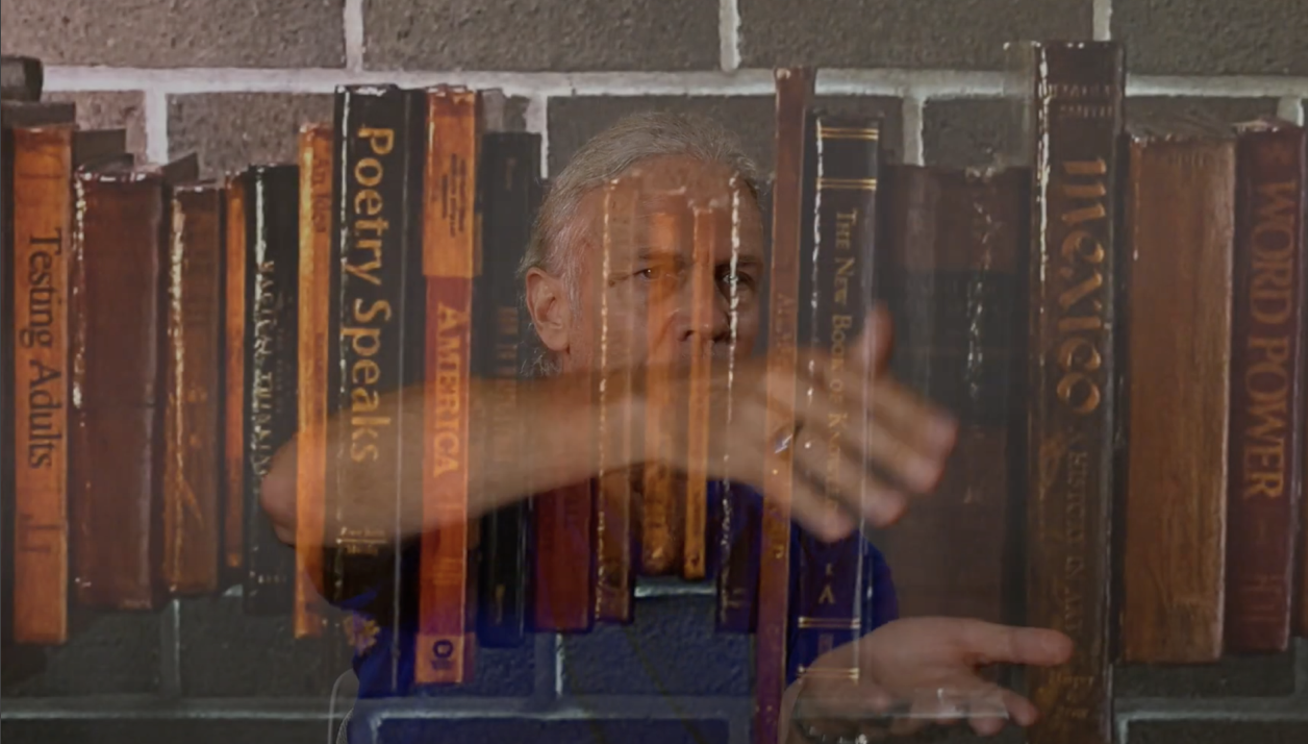

Thomas G. Carpenter Library Interview about "Suspended Sentence"

50th-Anniversary Celebration of the University of North Florida

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7I0CfVB63P8

50th-Anniversary Celebration of the University of North Florida

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7I0CfVB63P8

From an interview on the installation “Suspended Sentence":

1. Through your exploration of literature, poetry, performing and the visual arts, which element led you to the other? Or have they always coexisted with one another?

I suppose that it’s hard to disentangle the various forces that you list or, like the chicken and the egg, to determine which came first. I’ve always been a big reader, and yet the visual arts interested me greatly from a young age. I actually have an undergraduate degree in art history from the University of Kansas; it was only later—after years of living in New York, Europe and Japan—that I returned to graduate school in order to pursue an interdisciplinary MA and Ph.D. in the Modern Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

2. Where do you look for most of your inspiration? Is there a period in your life that you tend to look back on or are you always looking for new references?

Any inspiration that I gain comes from multiple sources that again reflect my interdisciplinary interests and background. So, certainly my various readings, the materials that I teach in the classroom at UNF (a lot of modern and contemporary poetry), art that I see during my travels, as well as a site-specific awareness of the landscape in which I might be working, all of these elements combine to create ideas and inspirations.

3. I see that you have a special interest in avant-garde art, how do you relay that message in your own work?

My interest in the avant-garde, an area of study that I teach at UNF, is based upon a desire to imagine new and unexpected ways of making art, placing art and thinking about art.

4. Your installations have a subtle yet bold presence. How do you decide on the placement of your words?

The placement of words for my various installations is determined greatly by whatever site that I am working within. At UNF, especially for the five “writing on water / writing on air” installations that I began in 2007, the university library (with its great stairway overlooking the pond) determined how the language was to be placed and seen; in my recent installation in Paris, at the Galerie Colbert, it also had to do with the site-specific dimensions of the project—the many interior windows that make up that powerful and historic space.

5. What is the significance of your poetry mixed with nature? What is the ultimate message you are trying to send the viewer?

I’m interested in integrating my poetry into and upon a particular setting or landscape. However, my work is, by design, nearly always short-term and ephemeral, making a mark upon the landscape that eventually fades away, leaving no trace of itself but the memories of the event. A message, if there is one, certainly involves these memoried traces, an awareness of time and place, and an embrace of the ephemeral.

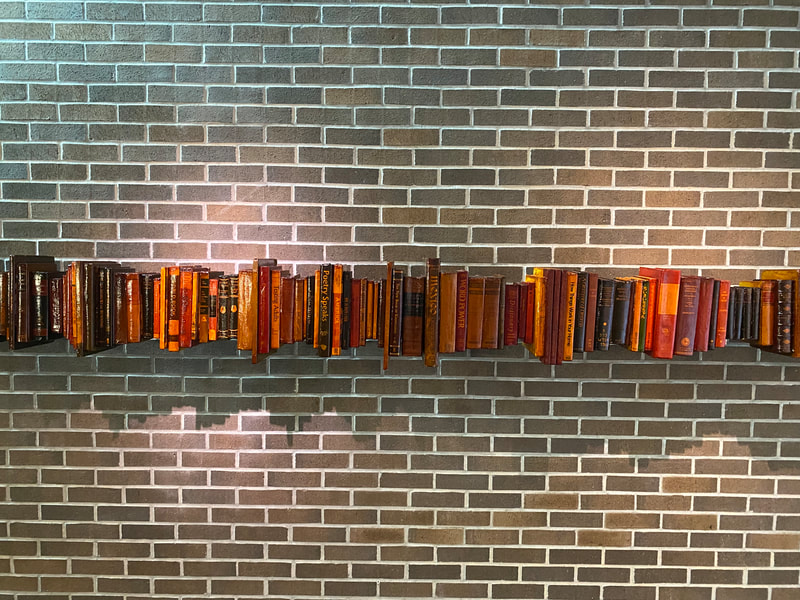

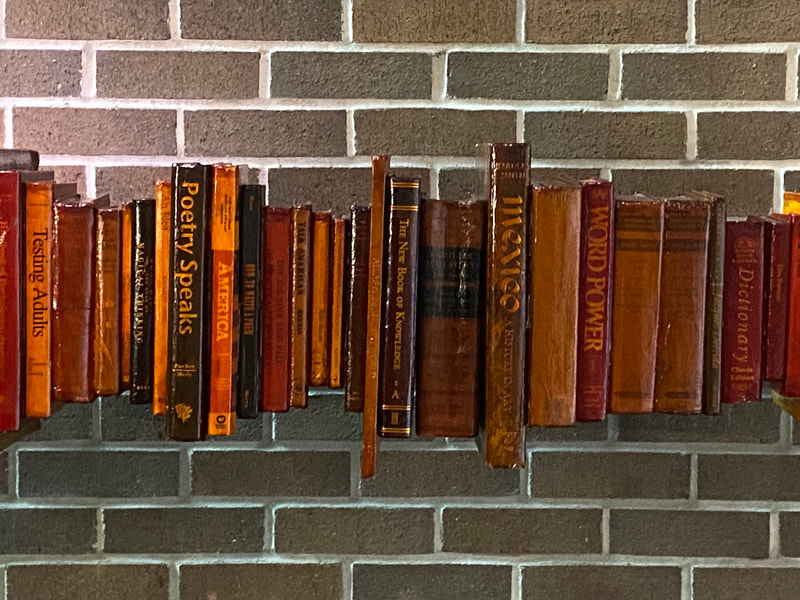

6. Your sculpture fro UNF's Art in the Library is different than your typical installations. Can you tell me a little about your intuitive and design process? How this one is similar and how is it different?

Yes, the recently installed piece at UNF, “Suspended Sentence,” is very different from my other installation work precisely because of its relative permanence as compared to my short-term installations on water and windows. This is a piece that will be attached to the library wall for many years to come, offering a more enduring presence than I am accustomed to engage.

As it was designed for the UNF library, commissioned by Dean Shirley Hallblade, I very much wanted to use books as a key part of the project, especially at this historical moment when libraries and books are in such a tenuous and transitional stage. The 103 books of this installation each had a two inch holes drilled into their centers; they were then laced onto a ten foot galvanized steel pipe which was then attached to the library’s brick wall; finally, all of the books were painted with eight coats of thick and luminous shellac. Like a long-forgotten mosquito trapped in ancient amber, the many books of my piece are now sealed together, suspended in time indefinitely from off of the brick wall.

7. I do see the trend of using literature among natural surroundings and the theme of bold subtlety in its placement and design. Are these key elements for you?

I like your formulation of “bold subtlety” and it describes something of what I seek—a simplicity of form that nonetheless resonates to a larger scale of awareness. The “writing on water” installations at UNF are an example—the pieces, as poems, are composed of only a few words, and yet each letter is anywhere from 8-10 feet in size. As such, there’s no mistaking, or even missing, their presence floating out on the water.

8. How would you say your creating these installations has reached the students on campus, in particular your students and those in other programs?

Much of my installation work involves really a kind of guerilla activity in which traditional spaces of exhibition are bypassed and, instead, my pieces are found in unexpected and surprising locations. Students are then confronted, or even obliged, to see the work (whether they like it or not) as they, for instance, climb the library stairs and look out its windows. I’m an English and not an art professor, and so I feel less beholden to or confined by more conventional exhibition expectations.

9. How do you strive to teach your students the art of literature and the possibilities beyond just being a great writer? Do you incorporate much of your experience in the arts as a teaching tool in the classroom?

I do occasionally bring up my own installation activity in the classroom, but only as a means to illustrate an issue or idea being dealt with by the material at hand. However, for all of my UNF installations, many students over the years have helped with the projects, often in very important ways—out in the kayak, scaling tall ladders and taping large letters onto windows... Any learning involved (and I believe that there is a lot) is, therefore, quite experiential and involves an awareness of language as material and the often long processes involved in my installations.

1. Through your exploration of literature, poetry, performing and the visual arts, which element led you to the other? Or have they always coexisted with one another?

I suppose that it’s hard to disentangle the various forces that you list or, like the chicken and the egg, to determine which came first. I’ve always been a big reader, and yet the visual arts interested me greatly from a young age. I actually have an undergraduate degree in art history from the University of Kansas; it was only later—after years of living in New York, Europe and Japan—that I returned to graduate school in order to pursue an interdisciplinary MA and Ph.D. in the Modern Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

2. Where do you look for most of your inspiration? Is there a period in your life that you tend to look back on or are you always looking for new references?

Any inspiration that I gain comes from multiple sources that again reflect my interdisciplinary interests and background. So, certainly my various readings, the materials that I teach in the classroom at UNF (a lot of modern and contemporary poetry), art that I see during my travels, as well as a site-specific awareness of the landscape in which I might be working, all of these elements combine to create ideas and inspirations.

3. I see that you have a special interest in avant-garde art, how do you relay that message in your own work?

My interest in the avant-garde, an area of study that I teach at UNF, is based upon a desire to imagine new and unexpected ways of making art, placing art and thinking about art.

4. Your installations have a subtle yet bold presence. How do you decide on the placement of your words?

The placement of words for my various installations is determined greatly by whatever site that I am working within. At UNF, especially for the five “writing on water / writing on air” installations that I began in 2007, the university library (with its great stairway overlooking the pond) determined how the language was to be placed and seen; in my recent installation in Paris, at the Galerie Colbert, it also had to do with the site-specific dimensions of the project—the many interior windows that make up that powerful and historic space.

5. What is the significance of your poetry mixed with nature? What is the ultimate message you are trying to send the viewer?

I’m interested in integrating my poetry into and upon a particular setting or landscape. However, my work is, by design, nearly always short-term and ephemeral, making a mark upon the landscape that eventually fades away, leaving no trace of itself but the memories of the event. A message, if there is one, certainly involves these memoried traces, an awareness of time and place, and an embrace of the ephemeral.

6. Your sculpture fro UNF's Art in the Library is different than your typical installations. Can you tell me a little about your intuitive and design process? How this one is similar and how is it different?

Yes, the recently installed piece at UNF, “Suspended Sentence,” is very different from my other installation work precisely because of its relative permanence as compared to my short-term installations on water and windows. This is a piece that will be attached to the library wall for many years to come, offering a more enduring presence than I am accustomed to engage.

As it was designed for the UNF library, commissioned by Dean Shirley Hallblade, I very much wanted to use books as a key part of the project, especially at this historical moment when libraries and books are in such a tenuous and transitional stage. The 103 books of this installation each had a two inch holes drilled into their centers; they were then laced onto a ten foot galvanized steel pipe which was then attached to the library’s brick wall; finally, all of the books were painted with eight coats of thick and luminous shellac. Like a long-forgotten mosquito trapped in ancient amber, the many books of my piece are now sealed together, suspended in time indefinitely from off of the brick wall.

7. I do see the trend of using literature among natural surroundings and the theme of bold subtlety in its placement and design. Are these key elements for you?

I like your formulation of “bold subtlety” and it describes something of what I seek—a simplicity of form that nonetheless resonates to a larger scale of awareness. The “writing on water” installations at UNF are an example—the pieces, as poems, are composed of only a few words, and yet each letter is anywhere from 8-10 feet in size. As such, there’s no mistaking, or even missing, their presence floating out on the water.

8. How would you say your creating these installations has reached the students on campus, in particular your students and those in other programs?

Much of my installation work involves really a kind of guerilla activity in which traditional spaces of exhibition are bypassed and, instead, my pieces are found in unexpected and surprising locations. Students are then confronted, or even obliged, to see the work (whether they like it or not) as they, for instance, climb the library stairs and look out its windows. I’m an English and not an art professor, and so I feel less beholden to or confined by more conventional exhibition expectations.

9. How do you strive to teach your students the art of literature and the possibilities beyond just being a great writer? Do you incorporate much of your experience in the arts as a teaching tool in the classroom?

I do occasionally bring up my own installation activity in the classroom, but only as a means to illustrate an issue or idea being dealt with by the material at hand. However, for all of my UNF installations, many students over the years have helped with the projects, often in very important ways—out in the kayak, scaling tall ladders and taping large letters onto windows... Any learning involved (and I believe that there is a lot) is, therefore, quite experiential and involves an awareness of language as material and the often long processes involved in my installations.

Copyright © 2015 Clark Lunberry. All rights reserved.