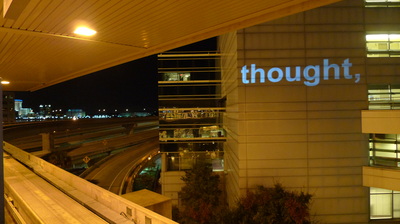

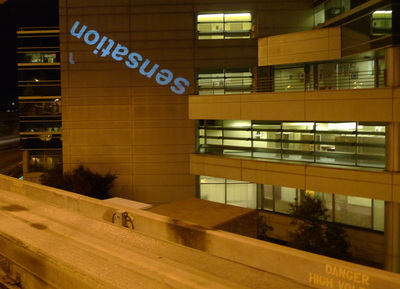

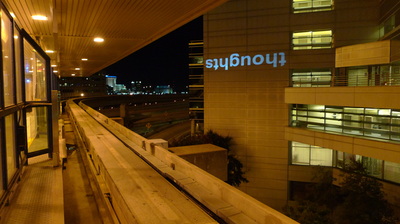

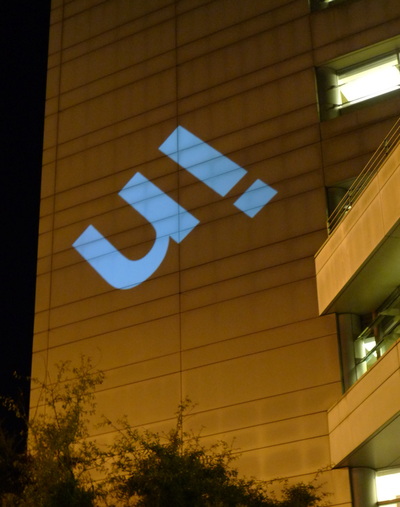

STATE OF GRACE

Installation at the San Marco Skyway Station

Jacksonville, Florida

December 1, 2010

“The artist must never have an idea, a thought, a word in mind when he needs a sensation.

Great words are thoughts that don’t belong to you.”

-Paul Cézanne, as recalled and reconstructed by Joachim Gasquet

Great words are thoughts that don’t belong to you.”

-Paul Cézanne, as recalled and reconstructed by Joachim Gasquet

Paulo Véronèse, Les Noces de Cana

Paulo Véronèse, Les Noces de Cana

“A state of grace in colors….”

On the subject of seeing light and feeling its rich and storied sensation (and knowing that you have seen it because you saw yourself see it, and then said so), I am reminded of a story involving the French painter Paul Cézanne. As is well known, Cézanne was an artist fascinated by a volcanic mountain, Mt. Ste. Victoire in the south of France, painting it again and again over many years. As the story goes, Cézanne was standing with the poet Joachim Gasquet in the Louvre before Paulo Véronèse’s monumental and very noisy-looking masterpiece Les Noces de Cana — with all that murmur and chatter depicted in paint — and whispering in his young friend’s ear: “Listen, it is breathtaking! What are we? Close your eyes, wait, don’t think about anything. Open them…All you see is the great colored wave, hmm? — an iridescence, colors, a richness of colors. That is what painting should give us, a harmonious warmth, an abyss into which the eye can sink, a silent germination. A state of grace in colors…. You have to know how to see, to feel, especially in front of a great machine such as the one Véronèse built” (qtd. in Doran 132-133).

It is instructive to note that Cézanne begins by insisting that his companion “listen!” not look at Véronèse’s busy (buzzing) painting, to close his eyes — as if any seeing of the painting is to begin by hearing it — and by first expansively wondering (in the “breathtaking” darkness), “What are we?”

But how, one wonders, is Cézanne’s companion ever to respond to such a weighty and unexpected question (coming, as it does, as if from “out of the blue”)? For would not the artist’s words only gracelessly get in the way of the painter’s described “state of grace,” a state arising from the warm and harmonious condition induced by Véronèse’s “great machine”? And, even more noisily, would not Cézanne’s words only muck up the machinery of this “built” painting, grinding that grace to a screechy halt?

Indeed, as Cézanne elsewhere makes clear, in order to enter such an iridescent and silently germinating abyss, “the artist must never have an idea, a word in mind when he needs a sensation. Great words are thoughts that don’t belong to you” (qtd. in Doran 116).

However, of this moving story in the museum, one should perhaps acknowledge that the precision and power of Cézanne’s own quoted words are, in fact, somewhat dubiously attributed to the painter by his friend, the poet Gasquet. For, in a time period prior to the existence of recording equipment, Gasquet was obliged to write from recollection what Cézanne had earlier said in the museum, placing into narrative form the remembered engagement in the gallery.

One might, therefore, reasonably suspect that Gasquet was at least partially prompting the painter, after the fact, to a command of language, a “literary” eloquence that, by most accounts, Cézanne did not possess and of which he was reportedly quite suspicious and dismissive. Indeed, describing his desire as a painter to “make one feel the air” (Doran 29), Cézanne spoke (or, again, is said to have spoken) of the need to “think without words” (Doran 124) and stated that “conversations about art are almost always useless” (Doran 30).

Consequently, one might imagine that if, in the Louvre, Cézanne was, in real time, prompting the eyes of the poet Gasquet to see (via language) the painting before him, it was Gasquet who was then later prompting the prompter, Cézanne, to speak, via the poet’s voluntary recollection and embellished reconstruction, “thoughts that [may have not quite] belong[ed] to [him].”

On the subject of seeing light and feeling its rich and storied sensation (and knowing that you have seen it because you saw yourself see it, and then said so), I am reminded of a story involving the French painter Paul Cézanne. As is well known, Cézanne was an artist fascinated by a volcanic mountain, Mt. Ste. Victoire in the south of France, painting it again and again over many years. As the story goes, Cézanne was standing with the poet Joachim Gasquet in the Louvre before Paulo Véronèse’s monumental and very noisy-looking masterpiece Les Noces de Cana — with all that murmur and chatter depicted in paint — and whispering in his young friend’s ear: “Listen, it is breathtaking! What are we? Close your eyes, wait, don’t think about anything. Open them…All you see is the great colored wave, hmm? — an iridescence, colors, a richness of colors. That is what painting should give us, a harmonious warmth, an abyss into which the eye can sink, a silent germination. A state of grace in colors…. You have to know how to see, to feel, especially in front of a great machine such as the one Véronèse built” (qtd. in Doran 132-133).

It is instructive to note that Cézanne begins by insisting that his companion “listen!” not look at Véronèse’s busy (buzzing) painting, to close his eyes — as if any seeing of the painting is to begin by hearing it — and by first expansively wondering (in the “breathtaking” darkness), “What are we?”

But how, one wonders, is Cézanne’s companion ever to respond to such a weighty and unexpected question (coming, as it does, as if from “out of the blue”)? For would not the artist’s words only gracelessly get in the way of the painter’s described “state of grace,” a state arising from the warm and harmonious condition induced by Véronèse’s “great machine”? And, even more noisily, would not Cézanne’s words only muck up the machinery of this “built” painting, grinding that grace to a screechy halt?

Indeed, as Cézanne elsewhere makes clear, in order to enter such an iridescent and silently germinating abyss, “the artist must never have an idea, a word in mind when he needs a sensation. Great words are thoughts that don’t belong to you” (qtd. in Doran 116).

However, of this moving story in the museum, one should perhaps acknowledge that the precision and power of Cézanne’s own quoted words are, in fact, somewhat dubiously attributed to the painter by his friend, the poet Gasquet. For, in a time period prior to the existence of recording equipment, Gasquet was obliged to write from recollection what Cézanne had earlier said in the museum, placing into narrative form the remembered engagement in the gallery.

One might, therefore, reasonably suspect that Gasquet was at least partially prompting the painter, after the fact, to a command of language, a “literary” eloquence that, by most accounts, Cézanne did not possess and of which he was reportedly quite suspicious and dismissive. Indeed, describing his desire as a painter to “make one feel the air” (Doran 29), Cézanne spoke (or, again, is said to have spoken) of the need to “think without words” (Doran 124) and stated that “conversations about art are almost always useless” (Doran 30).

Consequently, one might imagine that if, in the Louvre, Cézanne was, in real time, prompting the eyes of the poet Gasquet to see (via language) the painting before him, it was Gasquet who was then later prompting the prompter, Cézanne, to speak, via the poet’s voluntary recollection and embellished reconstruction, “thoughts that [may have not quite] belong[ed] to [him].”

Copyright © 2015 Clark Lunberry. All rights reserved.