500 Disciples of the Buddha | Go-Hyaku Rakan of Japan

(scroll down for an essay on the Go-Hyaku Rakan of Japan)

(scroll down for an essay on the Go-Hyaku Rakan of Japan)

Among the Buddha’s 500 Disciples: The Go-hyaku Rakan of Japan

By Clark Lunberry (1992)

“Frost on grass:

a fleeting form

that is, and is not.”

— Zaishiki (1642 - 1719)

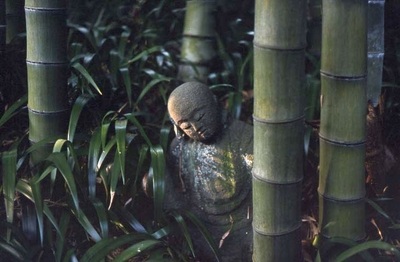

Off the well-beaten paths of the tourist itineraries of Japan, one can find remarkable but little-known groups of Buddhist statuary collectively referred to as the Go-hyaku Rakan (500 statues of the Buddha’s disciples). Rarely mentioned in guide books and scarcely documented or discussed, these enormous gatherings of statues are generally found adjacent to small, uncelebrated Buddhist temples and located in rural, out-of-the-way areas of the country. Sculpted in the native stone of the surrounding mountains, these carved figures are often hundreds of years old. From southern Kyushu to northern Honshu, to a tiny island in the middle of the Inland Sea, the 500 Rakan were created and maintained for the local temples. And yet, these sites have to this day remained for the most part unknown to the larger public and also ignored and neglected by scholars and art historians. In most cases, information about the statues or the sculptors who carved them has been lost and is now difficult or often impossible to obtain. However, though the facts and details have faded or disappeared, these remote sites and their remarkable rakan have survived.

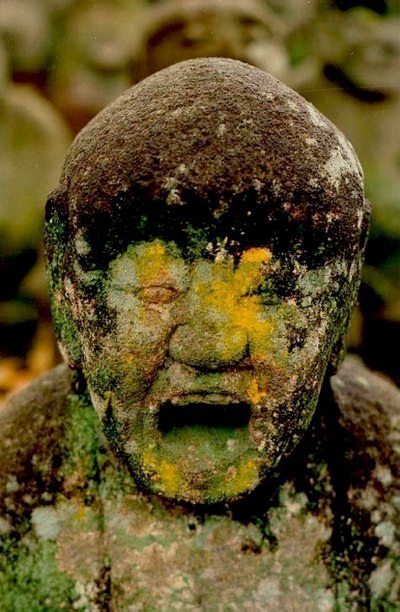

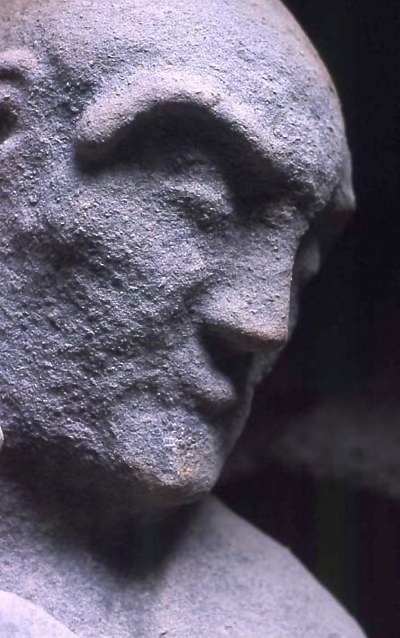

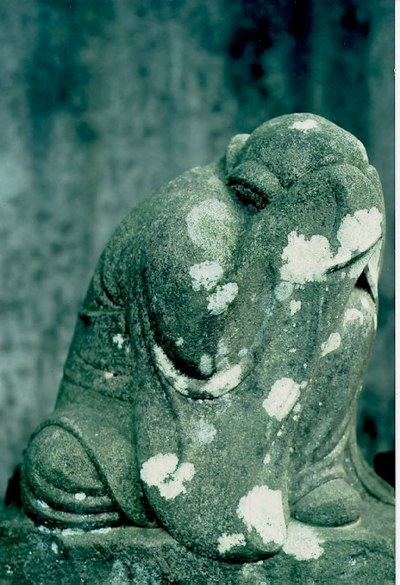

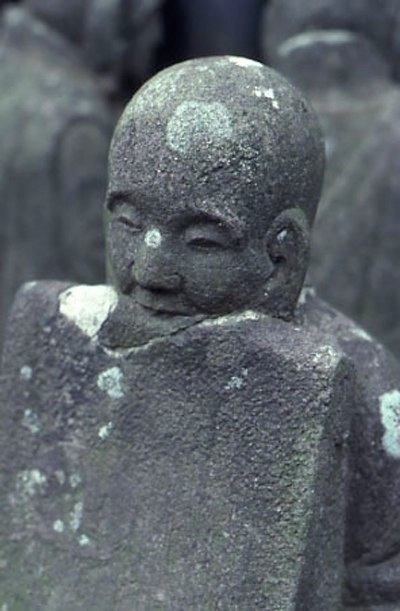

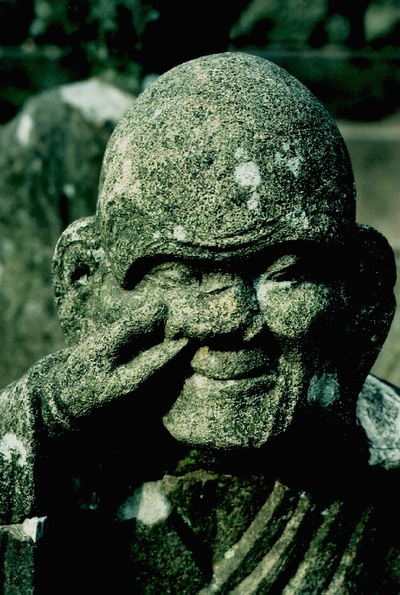

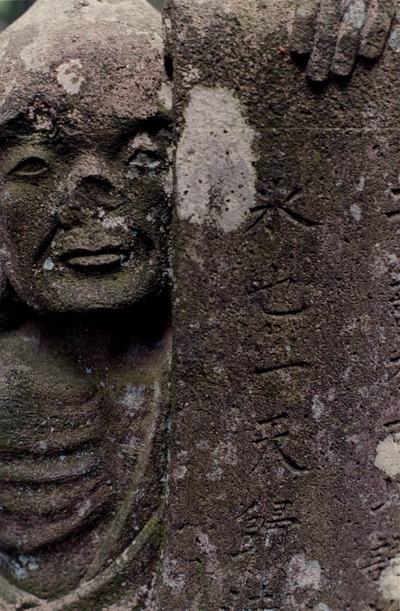

The statues of the disciples are generally found in either dense groupings—shoulder to shoulder, one along side another—or scattered widely along the trails and trees of a mountainside. In sharp contrast with the often uniform depictions of the stoic and enlightened Buddha, the rakan exhibit an extraordinary range of expression, personality, mood and gesture—attributes clearly more human than divine. Instead of the reverence and awe associated with images of the Buddha, the rakan seem both warm and approachable, perhaps an intermediary between the distant, divine Buddha and the struggling and suffering of humanity. Among the rakan, a broad range of individuals is represented, each possessing a particular personality with a distinctly pre-enlightened identity. Their gestures and expressions are known to us—the moods they impart have been shared, their physical features seen, their personalities encountered. Through the density of arrangement, there is often evoked a warmth of proximity and consolation, a vast community of familiar faces. Walking among the rakan occasions an intimate interaction and bonding of characters, alignments of flesh and stone that mysteriously and movingly join us to them.

Entering a site and abruptly confronting the 500 Rakan is to find oneself suddenly surrounded by an extraordinary number of individually sculpted figures. While wandering among the statues, a viewer’s focus easily and inevitably shifts back and forth from the single figure, the lone rakan, to that of the larger encompassing group—from the one to the many, from the many to the one. The astonishing variety found among the hundreds of statues attests to the prodigious skill and creative imagination of the original sculptors. Often regarded as an anonymous and isolated variation of what today would be called a kind of “folk art,” the artistic diversity and range of these stone sculptures reveals, however, both a formal and spiritual sophistication that belies their humble and obscure beginnings. Working with great power and expansive invention, the forgotten artists have created groups of figural images that poignantly exemplify the spirituality of Buddhism, while also interjecting some of the more animistic features of Japan’s native Shinto religion. Together, the statues combine to manifest the depths and detachments of Buddhism with the personal engagements of ancestral presence, a lineage of life manifested in stone.

From among the sites and the statues, various local legends and customs have formed. One story has it that the carefully observing visitor may find among the hundreds of figures one specific statue that most resembles him or her. At a location in central Japan, it is said that if you touch the statues in the dead of night, placing your hand upon each of the darkened stone heads, you are certain to discover one that is warm. By marking the statue and returning the next day, it is believed that this will be the sculpted figure most resembling yourself. And at another site, the story is similar. Looking closely at the range of faces and forms, one can perhaps find a figure resembling an ancestor or acquaintance who has long since died. It is not uncommon to see among the occasional visitors an almost studious interaction with the statues, a careful and sincere investigation of the stone’s silent suggestion.

The Japanese term rakan is derived from the Sanskrit arhat. Literally meaning “the worthy one,” the term was originally used as an epithet for the Buddha, and later in Theravada Buddhism for a Buddhist who had attained the highest rank of religious wisdom. The rakan stood as the spiritual ideal of early Buddhism, representing the perfected individual who has attained enlightenment and escaped from the cycle of rebirth. However, with the emergence of Mahayana Buddhism, the characterizations of the rakan developed and diversified, and by some accounts, diminished. Borrowing features from the compassionate bodhisattva, the rakan were occasionally portrayed as upholding and protecting the “Buddha-truth” and assisting all living beings in reaching enlightenment. And yet, on the other hand, they were sometimes presented in stories and legends in a more down-to-earth and humanly familiar manner—mere mortals struggling with their duties, devotions and desires. In some accounts, the rakan were depicted as weak and selfish, motivated by spiritual delusion and possessing, at best, a false enlightenment. In Zenno Ishigami’s book Disciples of the Buddha, we see that “not all the Buddha’s disciples were ‘model students’ from the start. Some gave in to sloth in the course of their religious practice and began to fall away, only to be reawakened by the admonitions of the Buddha and the more advanced disciples. Others reached a spiritual impasse and had to endure great mental suffering to attain enlightenment. Still others found themselves unable to sever their attachments to the world…; some joined the community of disciples and left it several times before finally attaining enlightenment.”

The rakan are generally found in groups of ten (the original disciples), sixteen, eighteen or five hundred. It was, however, the 500 Rakan who, according to legend, are said to have assembled immediately after the Buddha’s death to compile the Buddhist canon and establish monastic rules. From this, the principle collection of the Buddha’s teachings are believed to have taken shape. Early depictions of the rakan often portrayed them as austere, solitary ascetics or eccentric mountain hermits. In China, where the figures are called lohan, a virtual cult developed around them in the tenth century, beginning with sixteen disciples, but eventually expanding to eighteen and later five hundred. Paintings of these figures became popular during the Song and Yuan dynasties where they were often portrayed as strange, comic, grotesque or even frightening figures. With the transmission of Buddhism from China to Japan in the 6th century AD, an interest in and devotion to the disciples was also transferred and many Chinese paintings on this subject were copied and disseminated. It was, however, during Japan’s Tokugawa era (1600-1868), in what some believe was an attempt to make Buddhism both more popular and accessible to the general public, that the bringing together of all five hundred of the disciples into one large grouping of statues was developed—the Go-hyaku Rakan.

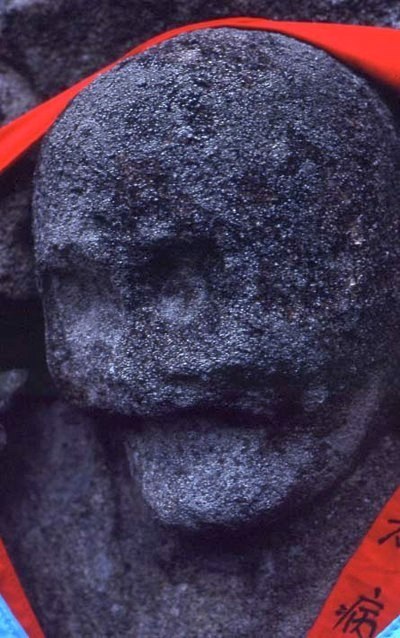

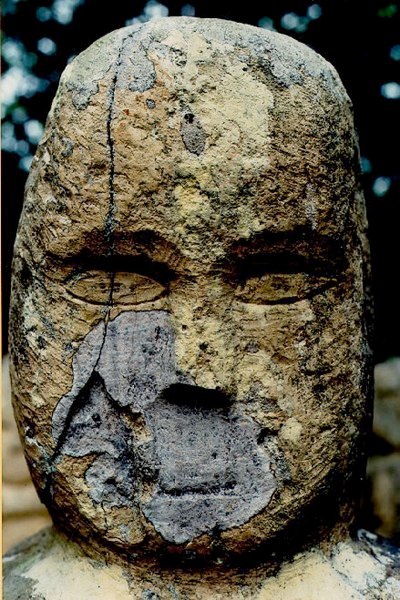

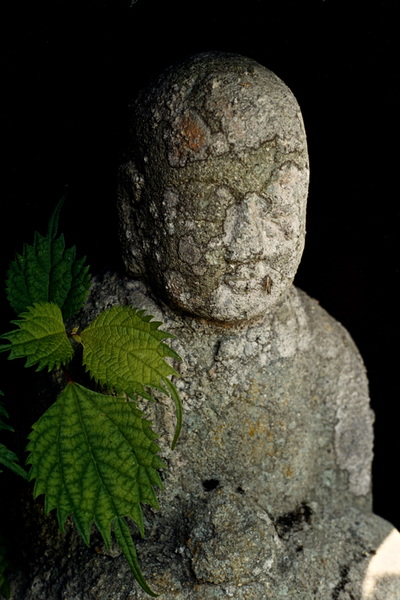

Looking closely at the individual rakan, one often sees an additional rich and poignant feature which has inadvertently developed over time. The 500 Rakan are generally found, not protected and preserved inside temples or museums, but rather they are left outside on the tops of mountains, in damp caves or canyons, or on open valleys. As the years have passed, the stone figure has changed and the rakan has been transformed from a finished statue to an aging object. The elements have conspired to distinguish further these already radically individualized statues, as time, climate, and the natural setting have slowly altered the carved image. The original rakan have been gradually re-created, and are indeed re-creating, as time and nature incessantly interact with the statue’s material, its surface and its form. Among and upon these statues, one often sees accumulated moss formations, crawling and clinging vines and stems, as well as cracks and crevices—a smoothing of the hard edges from the dissolution of the stone. Clearly, the natural setting of these rakan has not remained simply as a benign, neutral backdrop from which to view the statues. Indeed, nature has slowly encroached upon and entangled itself with the seemingly permanent, inert material of the stone figure. Distinguishing the statue from the stone becomes increasingly difficult as the limits and divisions between the cultural and the natural have slowly been effaced and withdrawn.

As devotional statues at a religious site, these aged and weathered rakan can be viewed from a particularly Buddhist point of view. One of the central teachings of Buddhism is the Principal of Impermanence (in Japanese: mujō; 無常). Dōgen, the great Sōtō Zen teacher, wrote, "...the very impermanence of grass and trees, thicket and forest, is itself the Buddha-nature. The very impermanence of men and things, body and mind, is the Buddha-nature. Nations and lands, mountains and rivers are impermanent because they are Buddha-nature." The rakan, also, in their distinctly time-worn condition, reflect and embody their own change, impermanence and loss, what Dōgen calls the "Buddha-nature." For, on the surface of the stone, one can read the trace of time and witness the subtle force of that nature. The curve of the brow, the form of the nose, the line of the mouth manifest an imperceptible motion in that which seems solid, seems unmoving, but which moves at a pace slower than the eye is accustomed to see. Looking closely at the fading form of the rakan, one can observe a stage in a process, a moment in a movement, the solid becoming soft. The incised lines of detail that determined and defined the carved image have become lost in the grain of the stone. The curves of the body have smoothed into subtle shadow as the form of the rakan slowly sheds their boundaries. From stone to image. From image to stone. What seemed to have been a very permanent stone object is, like everything else, impermanent and constantly transforming.

In most cases, the individual rakan has not entirely vanished; it has not crumbled to the ground nor faded entirely back into the surrounding earth. Instead, the figure has been changed and transfigured, progressing towards its own disappearance but not yet there, not yet gone. The direction and momentum of the transforming movement is understood, the laws of entropy intractable. With the incessant accumulation of time, the rakan will inevitably lose any suggestion of the human touch that originally formed it—the mortal image melting entirely back into the mortal stone. For now, however, the statue maintains a powerful and affecting presence that speaks of its own endurance while embodying its own impermanence and loss. A poignant image, a poetic moment, the Principal of Impermanence can been seen to manifest itself upon the material depictions of the Buddha’s faithful rakan.

Related Publications

"Enlightenment Needs a Minyan” (photographs). Tricycle: The Buddhist Review (Summer 1996): 48-52.

“Rakan: The Disciples of the Buddha” (photographs). Kyoto Journal 20 (Spring 1992): 31-35.

“Japanese Jizo” (photographs and article). Mainichi Graphic, 1 Oct. 1989: 35-42.

"Enlightenment Needs a Minyan” (photographs). Tricycle: The Buddhist Review (Summer 1996): 48-52.

“Rakan: The Disciples of the Buddha” (photographs). Kyoto Journal 20 (Spring 1992): 31-35.

“Japanese Jizo” (photographs and article). Mainichi Graphic, 1 Oct. 1989: 35-42.

Copyright © 2017 Clark Lunberry. All rights reserved.